The Wehe team has been collecting continuous data about net neutrality violations since January of this year, thanks

in large part to the more than 100,000 users of our Wehe app, who have collectively run 719,417 tests in 135

countries

around the world. We use an extensively validated, peer-reviewed

approach for determining whether Internet service

providers (ISPs) are giving different bandwidth to different applications (e.g., limiting the video resolution on

certain streaming video apps by limiting the bandwidth available).

We have spent the last several months analyzing this dataset to understand the state of net neutrality in the

networks our users tested, how exactly net neutrality is violated, and what are the potential implications. This

page presents a summary of our findings meant for a general audience. For technical details behind our analysis,

see our prior work and feel free to contact the Wehe team at

wehe@ccs.neu.edu with further questions.

Note: Wehe detects differentiation for an app by exactly replicating a tested app's network traffic, but it does not run the tested app directly. We are confident when detecting differentiation against a Wehe test, and it is likely that the corresponding app will also be affected. However, Wehe does not allow us to identify the exact impact of detected differentiation on the tested app. On November 11th, 2018, we updated this page to state these limitations and we updated language below to more clearly describe our test results.

Executive summary

We make the following observations. We go into more detail below.

- Nearly every US cellular ISP (CISP) throttles (i.e., sets a limit on available bandwidth) Wehe tests for at least one streaming video provider.

- No ISP in our tests throttles all the video providers in our tests, meaning some video providers may stream at higher resolution than others (potentially unfairly).

- Across the US, there is a wide range of observed throttling rates (i.e., bandwidth limits) set by CISPs. In some cases, the same CISP may use multiple throttling rates depending on the user’s service plan. This can make it difficult for video providers to give their users a uniformly high quality streaming session across different networks.

- The FCC rules permitting net neutrality violations went into effect on June 11th. Our data shows that all of the US CISPs that throttle after June 11th were already using some form of throttling prior to this date. In short, it appears that US CISPs were ignoring the Wheeler FCC rules pertaining to “no throttling” while those rules were still in effect.

- Throttling is not limited to content providers. We found that Wehe tests for a video call using the telephony app Skype are throttled by Sprint and Boost.

- We investigated the Sprint cases and found them to occur mainly for Android users. We are confident of the detected throttling, but cannot reproduce this behavior in the lab so we do not know why it is so prevalent for Android.

- This throttling was detected regularly over the course of the year, and spread geographically across the US.

- We observed that T-Mobile has implemented what we call “delayed throttling” behavior that is targeted at specific video streaming apps.

- With “delayed throttling” T-Mobile removes throttling for the beginning of a video streaming session. After a fixed number of bytes have been transferred, T-Mobile throttles the connection.

- Different apps get different amounts of delayed throttling, and YouTube gets none.

- Our analysis indicates that such delayed throttling detrimental to the video streaming session by causing network inefficiencies and confusing bitrate adaptation.

Summary of detected throttling

Below is a table that shows, for each ISP and app tested:

- What kind of network (WiFi or celluar) was tested

- Whether we detected throttling

- What throttling rate(s) we detected

- How many users and tests we used to make these claims

- How this behavior changed after June 11th, 2018 (i.e., when the new FCC rules took effect)

For each ISP, we included tests only where a user's set of tests indicated differentiation for at least one app and did not detect differentiation for at least one other app. This helps to filter out many false positives. As a result, the number of tests in this table is substantially lower than the total number of tests our users ran.

We sorted the CISPs based on the number of tests from our users in each ISP. If we did not detect differentiation, we

use the entry “Not detected.” This means we have sufficient tests to indicate that throttling is not happening. In

some cases we do not have sufficient tests to confirm whether there is throttling, indicated by “No data.”

The table has two column groups for our results: before the new FCC rules took effect on June 11th, and after. If

behavior changed from after June 11th, we highlight the case using a pale yellow background.

Use the drop-down menus below to select specific ISPs to view, the default is show them all.

-

ISP App Before Jun 11th After Jun 11th Throttling rate (s) # tests # users* Throttling rate # tests # users*

Skype throttling

We found a significant number of instances of Sprint throttling our Skype tests. This is interesting because Skype’s telephony

service can be construed as

directly competing with the telephony service provided by Sprint. Below we provide visualizations of where, when, and

on what mobile OS we see this behavior.

You can use the drop-down menus below to select which tests to visualize: all tests, only those with/without

throttling, and/or only those from iOS/Android devices. The map, timeline, and bar charts will update automatically

based on your selection. You can also select a time range on the timeline graph to update which data is visualized

in the map and bar charts.

We found no specific correlation over time or geography, so this throttling does not seem to happen only at certain

times or locations. Note that the vast majority of cases come from Android devices. We believe this is partially due to the

bias in our dataset: most of our tests (84%) are from Android devices. However, while 16% of all tests were from iOS devices,

less than 4% of cases of throttling came from iOS devices. In short, Android devices nearly exclusively see throttling of our Skype tests,

and the bias in our dataset does not sufficiently explain why throttling affects Android devices with higher frequency.

While we have strong evidence of throttling of our users' Skype tests,

we could not reproduce this throttling with a data plan that we purchased from Sprint earlier this year. This may be because it affects

only certain subscription plans, but not the one that we purchased.

We asked Sprint to comment on our findings. Their reply was: "Sprint does not single out Skype or any individual content provider in this way."

Our test results indicate otherwise, particularly for video content providers where we were able to confirm targeted throttling of Wehe tests.

T-Mobile delayed throttling

We found that T-Mobile (US) provides unthrottled bandwidth at the beginning of a connection for certain video

providers

but not all. After investigating every other ISP, we found T-Mobile to be alone in this behavior. We refer to this

as “delayed throttling.”

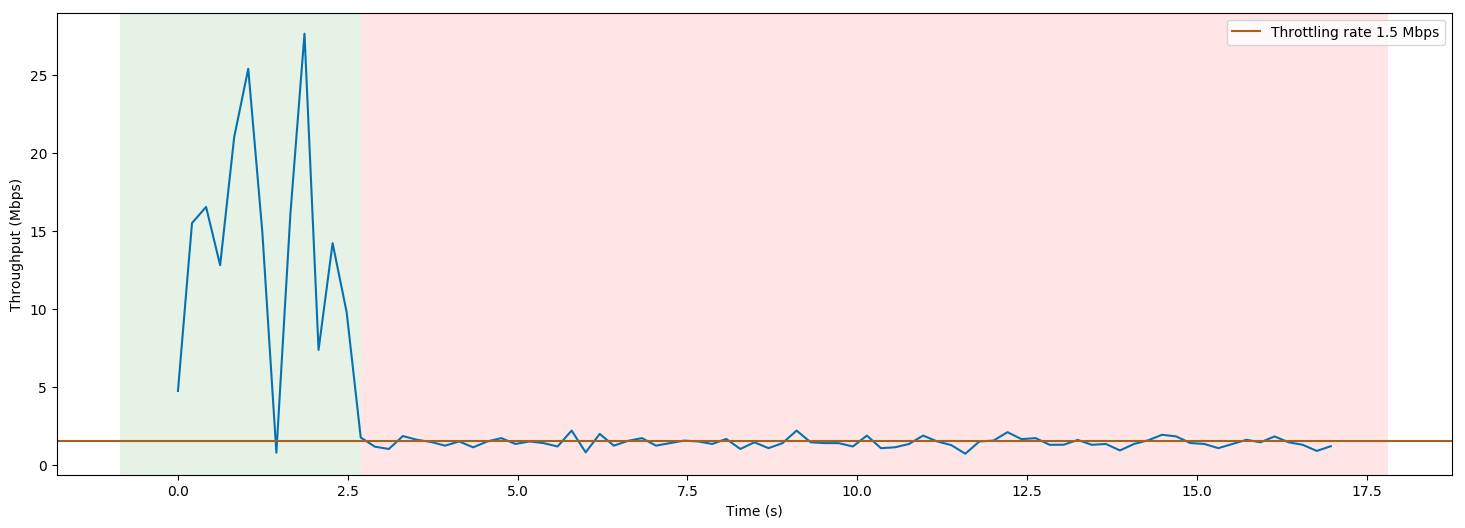

Below is an example graph of how fast (in megabits per second) an app can stream video data over time over T-Mobile.

Note that at the beginning of the transfer, we see speeds upwards of 25 Mpbs. However, after a few seconds the

transfer is throttled to 1.5Mbps (indicated by the horizontal line).

Through extensive testing, we found the throttling begins after a certain number of bytes have been transferred, and it is not based strictly on time; below we list the detected byte limits for the “delayed throttling” period.

| App | Delayed throttling bytes |

|---|---|

| Netflix | 7 MB |

| NBCSports | 7 MB |

| Amazon Prime Video | 6 MB |

| YouTube | Throttling, but no delayed throttling |

| Vimeo | No throttling or delayed throttling |

Note the cases of YouTube and Vimeo in the table above. T-Mobile throttles YouTube without giving it a delayed throttling period, while T-Mobile does not throttle Vimeo at all. Such behavior highlights the risks of content-based filtering: there is fundamentally no way to treat all video services the same (because not all video services can be identified), and any additional content-specific policies---such as delayed throttling---can lead to unfair advantages for some providers, and poor network performance for others.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the state of net neutrality today, and how it has evolved over the past year. In short, net neutrality violations are rampant, and have been since we launched Wehe. Further, the implementation of such throttling practices creates an unlevel playing field for video streaming providers while also imposing engineering challenges related to efficiently handling a variety of throttling rates and other behavior like delayed throttling. Last, we find that video streaming is not the only type of application affected, as there is evidence of Skype throttling in our data. Taken together, our findings indicate that the openness and fairness properties that led to the Internet's success are at risk in the US. We strongly encourage policymakers to use such analysis to help make more informed decisions about regulations that are based on empirical data.